WISCONSIN: WE’RE THE BEST AT LOCKING UP AFRICAN AMERICAN MEN – PART IV: BEHIND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE LEARNING CURVE

When it comes to criminal justice, Wisconsin is reacting instead of acting, coming slowly to innovation, and turning a blind eye to racial equality when meting out punishment. As a State, we’re behind the learning curve when it comes to crime and punishment, and sadly, some seem content with that. Despite a local university study finding that Wisconsin leads the nation by a very wide margin at incarcerating African American men, until recently there has been little debate by local political and criminal justice leaders on why we spend so much money incarcerating so many people in Wisconsin, with such unequal results for black men.

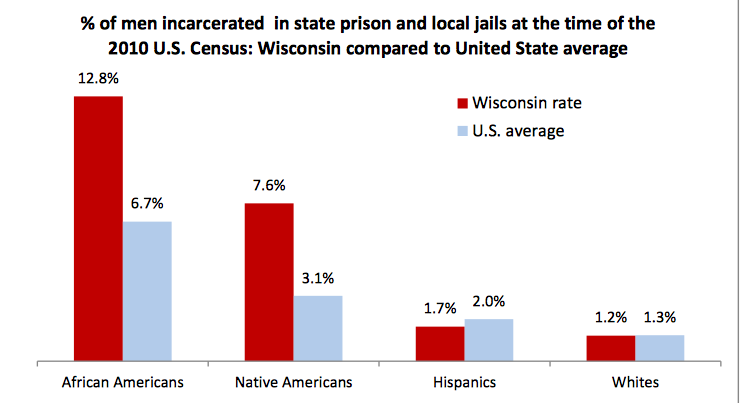

Last year on Martin Luther King Day, we highlighted a study by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee revealing that 1 in 8 of Wisconsin’s working age black men, or 12.8%, was behind jail or prison bars as of the last census count, compared with a national average of 1 in 15, or 6.7%. Wisconsin leads the nation in locking up black men, at a rate double the national average, and far higher than the next closest state. Since that time, we’ve written on why we don’t talk about this, on whether black life is cheaper in the justice system, and we’ve compared our prison expenditures with neighboring Minnesota. To mark this year’s holiday honoring Dr. King, we are compelled to continue writing, and explore how we’ve gotten here.

To come to a better understanding of what happened to African-Americans in Wisconsin, we first have to look at the state's recent criminal justice policy pattern affecting the larger population. Some quick numbers for comparison purposes: Wisconsin’s prison population currently exceeds 21,900 inmates, and the Wisconsin Department of Corrections budget exceeds 1.16 billion dollars. Minnesota’s prison population currently exceeds 9,900 inmates, and the Minnesota Department of Corrections budget exceeds 487 million dollars. Both states have similar populations, racial makeup, and crime rates, but Minnesota locks up less than half as many people, at far less than half the cost. So what happened on Wisconsin’s path to justice?

One factor was the local response in the 1990’s to the so-called War on Drugs. In Wisconsin, this resulted in district attorneys across the State – including large-population Milwaukee and Waukesha Counties – taking a one-size-fits-all approach in drug dealing cases by recommending prison sentences in all felony cases, no matter how small the amount of drugs involved or how marginally-involved the accused dealer was. Driven by federal funding for police multi-jurisdictional drug task forces, drug arrests and prosecutions got more plentiful and much more aggressive, with prosecutors refusing to reduce charges, or to recommend non-prison alternatives like probation. As a result, people went to prison for non-violent drug offenses in far greater numbers.

Another factor was the 1998 Wisconsin Truth in Sentencing law, which replaced Wisconsin’s previous system of indeterminate prison sentences adjusted by a parole board for positive behavior, or “good time”, with determinate sentences set by judges and no good time available at all. Prison inmates could no longer reduce their sentences by completing rehabilitative programming aimed at helping them become lawful members of society when released. Truth in sentencing passed with wide support, in response to the perceived need to treat crime victims and families fairly by making prison sentences definite, but despite an actual trend downward in the state crime rate in the five years preceding its passage. As a result, the prison population again swelled.

Wisconsin’s Juvenile Justice Act, passed in 1996, lowered from 18 to 17 the age at which a youth accused of crime is considered an adult, and created a category of offenses for which children younger than 17 could be charged in adult court, bypassing juvenile court altogether. Wisconsin passed the new juvenile justice act despite criticism that its premise – that child offenders needed to be treated more like adults – cut against emerging brain development studies showing that consequential decision-making works differently in young people than in adults. This firm was among the critics of the Juvenile Justice Act in the early 2000's, raising concerns in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinal citing the research on juvenile brain development after representing a 10-year-old boy accused of homicide. As a result, the ranks of those eligible to go to adult prisons in Wisconsin grew.

The stepped-up drug war, truth in sentencing, and the juvenile justice act are a few examples of Wisconsin’s severe policy approach to crime during the 1990’s. Coming out of that decade and into the 2000's, Wisconsin – and particularly Milwaukee County – were slow to adopt criminal justice reforms catching on in other areas of the country, reforms like drug treatment courts, which sought to address the expanding net of people caught up in the war on drugs by offering alternatives to prison for people whose drug addiction fueled their criminal behavior.

The hyper-harsh 1990's and the slow-learning 2000's resulted in Wisconsin's moving behind the learning curve in criminal justice policy. Our prison population exploded as a result, from just under 7,000 prison inmates in 1990 to over 22,000 inmates in 2012. As a state, we’re paying for this, both in the Wisconsin Department of Corrections' budget (which surpassed the State's university system budget in 2011), but also in the high human and societal cost of incarcerating a large portion of our population in prisons that offer no incentive to rehabilitate. People come out ill equipped to reintegrate back into communities and avoid returning to a life of crime, increasing the chance of returning to prison on parole violations.

As Wisconsin moved to imprison more people generally, black men in particular went to prison at even higher rates. There is no single explanation for how Wisconsin ended up in the number one position at incarcerating black men. But in a culture that pushed an incarceration-first model and came slowly to reform initiatives, it is not surprising that African-Americans were impacted twice as harshly as the larger population. When the government endeavors to squeeze those accused of crime more tightly, it is our experience at M&C Law that minority members and the poor end up being far easier targets than non-minorities and the wealthy. With implicit bias affecting who the police target, how the DAs prosecute, and what punishments the judges impose, the numbers demonstrate what has happened to black men as a result, and it looks like this in Wisconsin:

Inequality in our justice system is not simply an injustice; it is a threat to our community. In large part, what makes the system work and keeps us safe is our submission to the criminal justice system: most people voluntarily obey the law, and the large majority of people accused of crime come to court voluntarily and surrender peacefully to the justice system. We trust in the fairness of that system, and the extent to which it is unfair is the extent to which we place ourselves at risk of people no longer obeying the law, or submitting to the justice system's outcomes. When we approach that point, as we have in Wisconsin, it's time to take a look at where we've gotten it wrong, and to get back ahead of the learning curve, or at least catch up to it.

Inequality in our justice system is not simply an injustice; it is a threat to our community. In large part, what makes the system work and keeps us safe is our submission to the criminal justice system: most people voluntarily obey the law, and the large majority of people accused of crime come to court voluntarily and surrender peacefully to the justice system. We trust in the fairness of that system, and the extent to which it is unfair is the extent to which we place ourselves at risk of people no longer obeying the law, or submitting to the justice system's outcomes. When we approach that point, as we have in Wisconsin, it's time to take a look at where we've gotten it wrong, and to get back ahead of the learning curve, or at least catch up to it.

Recently, there has been increased discussion among criminal justice system professionals on these issues. M&C lawyers participated in a discussion on race and the justice system at Marquette University on October 17, 2014, along with many other defense lawyers, prosecutors, and Milwaukee County Judges. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported on that gathering, the first of its kind in Milwaukee County, and a necessary first step in getting smart on criminal justice.

It has been a year since M&C Law took up writing about Wisconsin’s #1 ranking at locking up black men. In the coming year, we will continue to do so, and hopefully spur continued discussion on this topic.

Our Prior Posts on Race and the Wisconsin Criminal Justice System: